The promise is always the same: track this, measure that, optimize everything, and finally—finally—you’ll have your life under control. The apps multiply on your phone like digital weeds. Sleep scores, step counts, productivity ratings, mood trackers, habit streaks. Each one whispers the same seductive lie: if you just monitor yourself closely enough, you can engineer your way out of being human.

I’ve watched brilliant people turn themselves into walking spreadsheets, and I’m starting to think optimization culture isn’t the antidote to chaos—it’s a sophisticated form of self-harm.

The Illusion of Control

When everything feels uncertain, optimization offers something irresistible: the feeling that we’re doing something. Can’t control the economy? Track your expenses down to the penny. Can’t control your boss’s mood swings? Optimize your morning routine. Can’t control whether your kids will have a future on this planet? Well, at least you can hit your step count.

The metrics feel scientific, objective, safe. Numbers don’t judge—they just measure. But here’s what I’ve noticed: the people most obsessed with optimizing their lives are often the ones who trust themselves the least. They’ve outsourced their intuition to algorithms, their self-worth to scores, their sense of progress to streaks and badges.

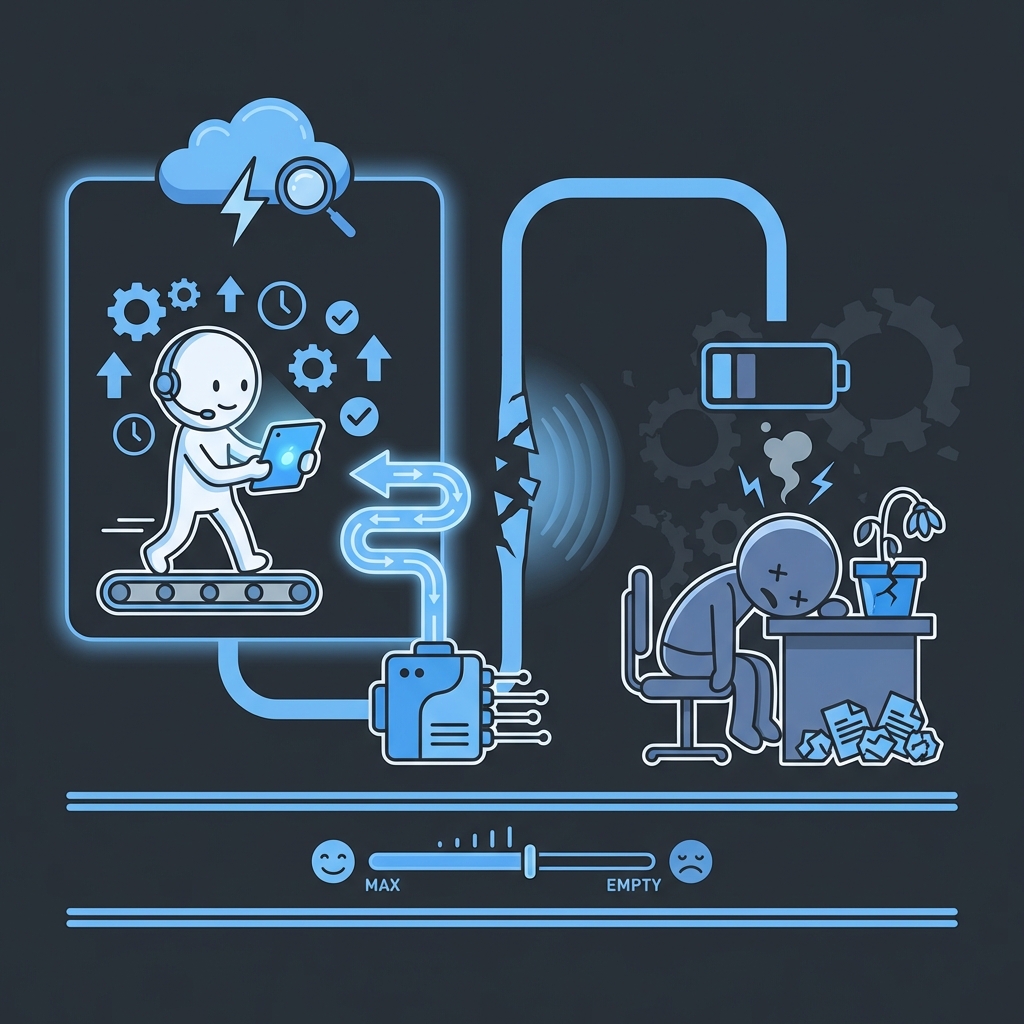

The cruel irony is that optimization culture promises control but delivers the opposite. Every new metric becomes a new way to fail. Every tracking system becomes a new source of anxiety. You start the day checking your sleep score, and if it’s low, you’ve already lost before you’ve even gotten out of bed.

The Expansion Problem

Optimization has a nasty habit of metastasizing. It starts innocent enough—maybe you want to drink more water or get better sleep. But optimization culture doesn’t believe in “enough.” There’s always another variable to track, another inefficiency to eliminate, another aspect of your humanity to quantify and improve.

First, it’s your physical health: steps, heart rate, calories, sleep cycles. Then your mental health gets the treatment: mood ratings, meditation minutes, gratitude entries, anxiety levels. Your relationships become “connection time” and “quality interactions.” Your work becomes “deep work blocks” and “productivity scores.” Even your leisure gets optimized—reading goals, learning streaks, hobby progress bars.

The goal posts don’t just move—they multiply.

I know someone who spent six months optimizing her morning routine. She tracked wake time, caffeine intake, exercise duration, meditation minutes, journaling words, and breakfast protein content. The routine took two hours and required four apps to manage. She was miserable, but her metrics looked great. When I asked if she felt better, she paused and said, “I don’t know. I haven’t been tracking that.”

This is what optimization culture does: it trains you to mistake measurement for improvement, monitoring for caring, data for wisdom. You become an expert at tracking your life while forgetting how to live it.

The Hidden Costs

The real tragedy isn’t just the time lost to tracking and tweaking—though that’s considerable. It’s what gets sacrificed on the altar of efficiency: spontaneity, presence, the messy beauty of being human.

Optimization culture teaches you to see slack as waste, inefficiency as failure, “good enough” as giving up. But slack isn’t waste—it’s where life happens. It’s the buffer that allows for conversation to meander, for inspiration to strike, for rest to actually restore you. It’s the space between what you planned and what actually unfolds.

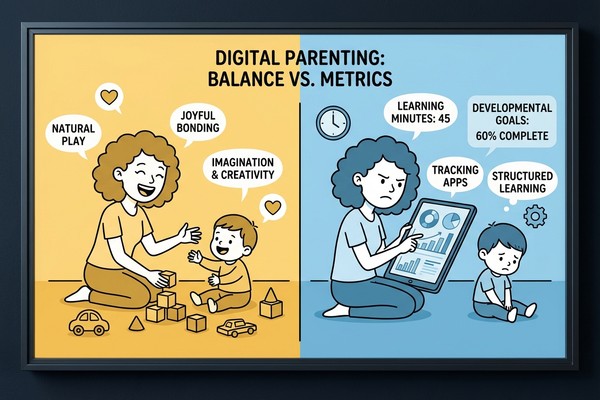

I think about the parents who optimize their children’s schedules down to the minute, tracking developmental milestones like stock prices. What gets lost isn’t just childhood—it’s the parent’s ability to simply enjoy their kid. Every interaction becomes a data point, every moment a missed opportunity for improvement.

Or the professionals who gamify their work, turning every task into a productivity score, every day into a performance review. They become incredibly efficient at doing things that don’t matter, optimized for metrics that have nothing to do with actual value or satisfaction.

The hidden cost is presence itself. When you’re constantly monitoring, you’re never fully where you are. Part of your attention is always split, observing and evaluating rather than experiencing and enjoying.

Why Humans Need Slack

Here’s what optimization culture gets fundamentally wrong: humans aren’t machines to be tuned. We’re complex systems that require inefficiency to function well. We need downtime that doesn’t count as “recovery.” We need conversations that go nowhere productive. We need space to be bored, to wander, to waste time in ways that feel good.

Slack isn’t a bug in the human system—it’s a feature. It’s where creativity lives, where relationships deepen, where wisdom emerges. The most important insights rarely come during “deep work blocks.” They come in the shower, on walks, in random conversations that started about nothing and ended up changing everything.

But optimization culture has trained us to feel guilty about slack, to see unstructured time as a failure of planning, unproductive moments as opportunities missed. We’ve internalized the machine metaphor so deeply that we feel broken when we need things machines don’t need: rest, play, connection, meaning.

Good enough isn’t giving up—it’s growing up.

The people I know who seem most alive, most present, most genuinely successful? They’re not the ones with the most optimized systems. They’re the ones who’ve learned to protect their slack, who understand that some things are too important to be measured, who’ve made peace with being beautifully, imperfectly human.

Reclaiming ‘Good Enough’

What if we treated “good enough” not as a consolation prize, but as a design principle? What if we built lives that worked well enough to support what actually matters, rather than systems so optimized they crowd out everything we optimized them for?

This isn’t about lowering standards—it’s about choosing them more carefully. Instead of trying to optimize everything, what if we identified the few things that genuinely matter and let everything else be good enough? Instead of tracking seventeen different metrics, what if we paid attention to how we actually feel?

The shift requires unlearning some deeply embedded cultural programming. We’ve been taught that more data leads to better decisions, that measurement equals caring, that optimization is always good. But sometimes the most caring thing you can do is stop tracking. Sometimes the best decision is made with intuition, not data. Sometimes optimization is just procrastination wearing a lab coat.

I’m not suggesting we abandon all structure or stop trying to improve. I’m suggesting we question who benefits when we treat ourselves like problems to be solved rather than people to be supported.

What Metric Are You Tired of Living Under?

Take a moment to consider: what number has too much power over your day? What score determines your mood before you’ve even had coffee? What streak makes you feel guilty when it breaks?

Maybe it’s the step counter that makes you pace around your living room at 11 PM. Maybe it’s the productivity app that rates your focus and finds you lacking. Maybe it’s the sleep tracker that tells you you’re tired before you’ve even noticed how you feel.

What would happen if you deleted that app? If you stopped checking that number? If you trusted yourself to know when you’re tired, when you’ve moved enough, when you’ve worked enough?

The fear, of course, is that without the external measurement, you’ll fall apart, become lazy, lose all progress. But here’s what I’ve observed: people who step back from optimization often become more effective, not less. They make better decisions because they’re paying attention to what actually matters rather than what’s easy to measure.

Systems That Protect Slack

The alternative to optimization culture isn’t chaos—it’s designing systems that serve you rather than systems you serve. Instead of tools that demand constant feeding with data, what if we chose tools that actually reduced our mental load?

This means systems that remember things so you don’t have to, that handle follow-up automatically, that work in the background rather than demanding your constant attention. It means choosing tools based on how much they reduce your cognitive burden, not how many metrics they can track.

The best system is the one you forget you’re using.

Real support looks like systems that create space for what matters rather than filling every moment with optimization. It looks like tools that handle the remembering, tracking, and following up so you can be present for your actual life.

The goal isn’t to become a more efficient machine. It’s to become a more fully realized human being. And that requires protecting the slack, embracing good enough, and remembering that the point of having a life isn’t to optimize it—it’s to live it.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.