You know that feeling when someone asks you a simple question and suddenly you’re rifling through three different mental filing cabinets? “Where did we put the warranty for the dishwasher?” sends you spiraling through purchase dates, email confirmations, and that one drawer where important papers go to die. Meanwhile, the person asking has already moved on to making coffee, completely unaware they just handed you a fifteen-minute research project.

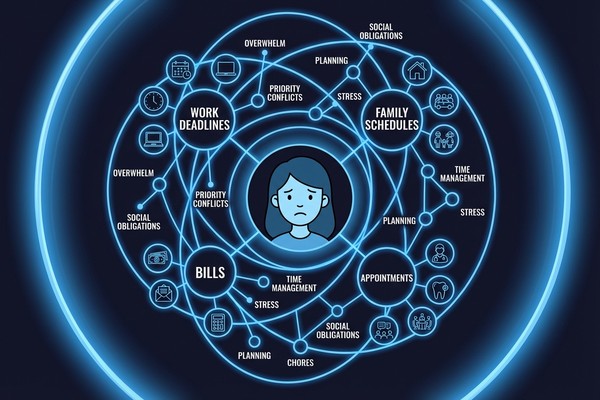

This is what carrying context looks like. It’s not just remembering facts—it’s maintaining the entire ecosystem of information that makes life function. Context is the invisible infrastructure that holds everything together, and if you’re reading this, you’re probably the one building and maintaining it.

What Context Really Means

Context isn’t just memory. It’s the complete picture: the current state of things, how we got here, what needs to happen next, and all the constraints that shape those decisions. It’s knowing that we can’t schedule the dentist appointment on Thursdays because that’s when Mom has physical therapy, and we need to book it before the insurance deductible resets, and Dr. Martinez is the only one who takes our plan.

When you hold context, you’re not just storing information—you’re maintaining the relationships between pieces of information. You know why certain decisions were made, what didn’t work last time, and which solutions are off the table because of circumstances others have forgotten or never knew.

This kind of comprehensive awareness feels natural when you’re living it, but it’s actually sophisticated cognitive work. You’re running a personal knowledge management system that would make corporate databases jealous. The problem is, nobody recognizes it as work—including you.

Where Context Lives (Everywhere)

Context infiltrates every corner of life. At home, you know which kid needs which permission slip signed by when, that the washing machine makes that noise when it’s overloaded, and that we’re out of the good pasta sauce but not the kind nobody eats. You remember that your partner mentioned wanting to try that new restaurant, filed away three weeks ago in a casual conversation.

At work, you’re the one who remembers why the client prefers email over calls, which vendor always delivers late, and that the quarterly report needs the data formatted differently this year because of the software change. You know the unwritten rules, the political landmines, and the workarounds that keep everything moving.

Your health context includes not just your own medical history, but your family’s. You know your mom’s medication schedule, your child’s allergy triggers, and which insurance forms need to be submitted by month-end. You remember symptoms, track patterns, and manage the complex choreography of multiple people’s wellness.

The context you carry isn’t just information—it’s the connective tissue that holds life together.

Relationships require perhaps the most delicate context management. You remember your friend’s job stress, your neighbor’s divorce timeline, and your sister’s complicated feelings about the holidays. You know who can’t be in the same room together at family gatherings and why, who’s struggling financially but too proud to say so, and which topics are off-limits with which people.

The Interruption Tax

Being the context-holder makes you a target for interruptions, and here’s the cruel irony: the more reliable you are, the more you get interrupted. People know you’ll have the answer, or at least know where to find it. So they come to you first, bypassing their own problem-solving process entirely.

“Where is the thing?” becomes your most-heard question. Not “Do you know where the thing might be?” or “Can you help me figure out where the thing is?” Just the expectation that you’ll produce the answer immediately, as if you’re a human search engine with instant access to all information.

These interruptions aren’t just about the time they take—though that adds up quickly. They’re about the cognitive switching cost. Each question pulls you out of whatever you were doing and forces you to access a completely different mental filing system. By the time you’ve found the warranty information, you’ve lost your train of thought on the project you were actually working on.

The worst part? People often judge context-holders more harshly when they don’t have immediate answers. If you usually know everything, the one time you don’t becomes a failure rather than a normal human limitation. The person who never remembers anything gets a pass, but your occasional blank stare gets met with surprise and disappointment.

The Emotional Weight of Being Essential

There’s a particular kind of pressure that comes with being the person everyone relies on for information. It’s not just the cognitive load—it’s the emotional responsibility of knowing that if you drop the ball, other people’s lives get disrupted.

You start to feel guilty for forgetting things that aren’t even your responsibility. You internalize the expectation that you’ll remember everything, and when you don’t, it feels like a personal failing rather than a systems problem. The mental load becomes self-reinforcing: you remember more because you feel responsible for remembering more, which makes others rely on you more, which increases your sense of responsibility.

This dynamic is particularly pronounced for women, who are often socialized to be the family’s emotional and logistical coordinators. The expectation that you’ll handle the “remembering work” isn’t usually explicit—it just gradually becomes your job because you’re good at it, or because you care about the outcomes, or because someone has to do it and you’re the most reliable option.

But being essential isn’t the same as being valued. The context you maintain is often invisible until something goes wrong. Nobody notices the smooth functioning you enable—they only notice when the system breaks down.

What Shared Context Actually Looks Like

In healthy systems, context isn’t concentrated in one person. Instead, it’s distributed and accessible. Everyone knows where to find information, how to update it, and takes responsibility for maintaining their piece of the puzzle.

Shared context means that when someone asks “Where is the thing?” the answer isn’t automatically your problem to solve. It means systems are documented, decisions are recorded, and the mental work of remembering is acknowledged as actual work that needs to be distributed fairly.

In families, this might look like shared calendars that everyone maintains, not just consults. It means teaching kids to remember their own schedules and responsibilities rather than relying on parents as backup memory. It means partners who take ownership of their domains instead of treating you as the project manager for everything.

At work, shared context means documentation that actually gets updated, knowledge that isn’t trapped in one person’s head, and systems that don’t collapse when someone goes on vacation. It means recognizing that the person who “just knows everything” is actually doing significant unpaid labor that should be systematized.

True collaboration isn’t just dividing tasks—it’s sharing the cognitive load of keeping track.

The Relief of Ambient Context

The most profound relief comes when context can be held outside your head entirely—not just shared with others, but maintained by systems that don’t require your constant attention. This is what ambient context feels like: the information is there when you need it, updated when things change, and accessible without requiring you to be the intermediary.

Imagine not being the family’s human search engine. Imagine not having to maintain the complex mental map of everyone’s schedules, preferences, and constraints. Imagine being able to forget things without feeling guilty, because the information is safely held somewhere else.

This isn’t about becoming less caring or less involved—it’s about freeing up your mental capacity for the things that actually require your unique human insight. When you’re not spending cognitive energy on remembering routine information, you have more space for creative problem-solving, deeper relationships, and simply being present.

The goal isn’t to remember nothing. It’s to remember what matters while letting systems handle the rest. It’s about recognizing that the context you carry has real weight, and that weight doesn’t have to be yours alone to bear.

The invisible work of keeping track deserves to be seen, valued, and most importantly, shared. Your mind is not a database, and treating it like one diminishes both your wellbeing and your actual capabilities. The context you’ve been carrying? It’s time to put some of it down.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.