You’re in the middle of a work presentation when your phone buzzes with a text from your mom about your dad’s upcoming surgery. Suddenly, you’re not just discussing quarterly projections—you’re also calculating drive times to the hospital, wondering if you should reschedule tomorrow’s meetings, and feeling that familiar knot in your stomach about family health scares. The spreadsheet on your screen blurs as your mind jumps to insurance coverage and whether your brother knows about the procedure yet.

This is spillover in action. And despite what productivity culture tells us, it’s not a bug in your system—it’s a feature of being human.

The Whole Person Problem

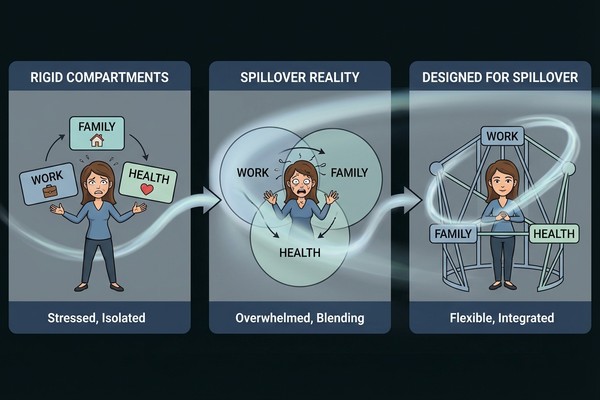

We’ve been sold a beautiful lie: that we can compartmentalize our lives into neat, separate boxes. Work stays at work. Family concerns pause during business hours. Health issues wait for convenient scheduling. Grief takes a designated timeline. Personal ambitions hibernate until we have “more bandwidth.”

But spillover doesn’t ask for permission. It shows up anyway, because the person experiencing work stress is the same person worried about their teenager’s college applications and managing their own anxiety about aging parents. The compartments we create are imaginary lines drawn on a life that refuses to be contained.

I watched a friend try to “leave her divorce at the door” during a crucial project launch. She showed up to every meeting, hit every deadline, and maintained her professional composure. But she also made uncharacteristic mistakes, forgot follow-up emails, and found herself staring blankly at her computer screen more often than she’d admit. The divorce wasn’t staying in its lane—it was affecting her ability to think clearly, remember details, and access her usual creative problem-solving skills.

The productivity industrial complex wants us to believe that spillover is a personal failing. That with enough discipline, the right apps, and better boundaries, we can achieve perfect compartmentalization. This narrative is not just unrealistic—it’s actively harmful. It transforms the natural human experience of having multiple, interconnected concerns into evidence of our inadequacy.

When Spillover Becomes Shame

The most insidious part of the compartmentalization myth is how it breeds shame. We start believing we “should be able to” leave work stress at work. We “should be able to” focus fully on family time without thinking about that presentation next week. We “should be able to” handle grief without it affecting our professional performance.

These “should be able to” statements are red flags. They signal places where we’re holding ourselves to impossible standards based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how human consciousness actually works.

The brain that worries about your mortgage is the same brain trying to solve problems at work. Expecting them to operate independently is like expecting your left hand not to know what your right hand is doing.

Consider the working parent who feels guilty for thinking about their sick child during an important meeting, then feels guilty for checking work emails during family dinner. They’re caught in a shame spiral created by the impossible expectation that they can toggle between completely separate selves throughout the day.

This shame compounds the original stress. Now you’re not just dealing with the actual challenges in your life—you’re also dealing with self-criticism for not managing those challenges “properly.” You’re carrying both the weight of your concerns and the weight of believing you shouldn’t have those concerns in the first place.

The Physics of Human Attention

Here’s what actually happens in your brain: attention is a limited resource that flows where it’s needed most. When your nervous system detects a threat—whether it’s a work deadline, a relationship conflict, or a health scare—it allocates cognitive resources accordingly. This isn’t a character flaw; it’s survival programming.

Your brain doesn’t distinguish between “work problems” and “personal problems.” It just sees problems that need solving, threats that need monitoring, and relationships that need tending. The executive function required to remember your mother-in-law’s birthday is the same executive function needed to track project deliverables. When one area demands more attention, other areas naturally receive less.

This is why you might find yourself unusually forgetful about routine tasks when dealing with a family crisis. It’s why relationship stress can make you less creative at work. It’s why physical pain can reduce your patience with your kids. The spillover isn’t random—it’s your brain doing exactly what it’s designed to do: prioritize and allocate resources based on perceived importance and urgency.

Understanding this can be profoundly liberating. Instead of fighting spillover, we can design our systems to accommodate it.

Designing for Spillover

What would change if we stopped trying to eliminate spillover and started planning for it? Instead of building systems that assume perfect compartmentalization, what if we built systems that expect the whole person to show up?

This starts with building buffers into our schedules and expectations. If you know that family stress affects your work focus, you might build extra time into project timelines during periods when family demands are high. If you know that work pressure makes you less patient at home, you might arrange for additional childcare support during busy seasons.

Triage becomes essential when we accept spillover as normal. Instead of trying to give equal attention to everything, we get strategic about what gets our best cognitive resources when. This might mean acknowledging that during your father’s cancer treatment, you’re going to be operating at 70% capacity at work—and that’s okay. It might mean recognizing that during a major project launch, family dinners are going to be more basic and that’s also okay.

The key is making these trade-offs consciously rather than pretending they don’t exist. When we acknowledge spillover, we can make intentional choices about where to direct our limited attention and energy.

The Support System Revolution

Designing for spillover also means building support systems that can flex with your changing needs. This might look like having a network of people who can step in when one area of your life demands more attention. It might mean choosing tools and systems that can adapt to your varying capacity rather than demanding consistent input.

Traditional productivity advice assumes you’ll show up the same way every day. But spillover-aware systems recognize that some days you’ll have the bandwidth to plan elaborate meals and some days you’ll need the cognitive load of dinner decisions completely removed. Some weeks you’ll be able to handle complex work projects and some weeks you’ll need your systems to carry more of the mental load.

This is where the rubber meets the road in terms of mental load reduction. Systems that only work when you’re operating at full capacity aren’t actually helpful—they’re just another thing to maintain when you can least afford the maintenance.

What Wholeness Actually Looks Like

Being whole doesn’t mean being perfectly managed. It means accepting that you’re a complex person with multiple, interconnected concerns that ebb and flow in importance and urgency. It means recognizing that your capacity varies and building flexibility into your expectations accordingly.

Wholeness might look like crying in your car after a difficult work meeting because you’re also processing your grandmother’s death. It might look like bringing your anxiety about your teenager’s mental health to your problem-solving approach at work. It might look like your creative project inspiring new approaches to a family challenge.

Spillover isn’t contamination—it’s integration. It’s proof that you’re living a connected life rather than a compartmentalized one.

The goal isn’t to eliminate the messiness of being human. The goal is to stop seeing that messiness as failure and start seeing it as information about what you need and where your attention is being called.

This Week’s Reality Check

Take a moment to notice where spillover is showing up in your life right now. Where are concerns from one area affecting your performance or presence in another? Instead of judging this as weakness, try seeing it as data about what’s important to you and what might need more support or attention.

Maybe work stress is making you shorter with your kids. Maybe relationship concerns are affecting your focus during meetings. Maybe health worries are making it harder to feel excited about future plans. These aren’t character flaws—they’re human responses to having multiple things that matter to you.

The systems that serve us best are the ones that expect spillover and plan for it. They’re designed for humans who have good days and bad days, who sometimes have the bandwidth for detailed planning and sometimes need their tools to think for them. They understand that the person managing work deadlines is the same person worried about their aging parents, excited about their creative projects, and trying to maintain their friendships.

When we stop fighting spillover and start designing for it, we create space for our whole selves to show up. And paradoxically, this often leads to better performance in all areas—not because we’ve achieved perfect compartmentalization, but because we’ve stopped wasting energy pretending it’s possible.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.