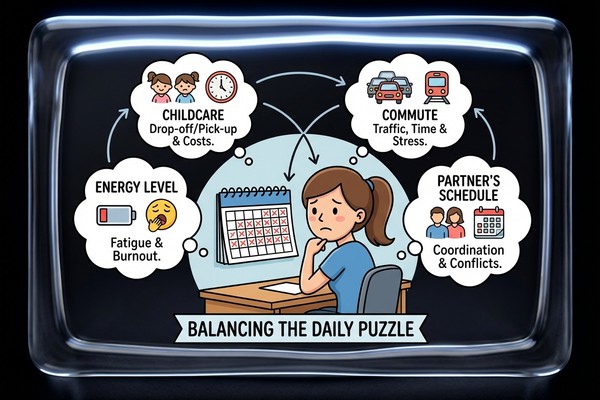

When someone asks if you’re free Thursday at 2 PM, what looks like a simple yes-or-no question actually triggers an entire invisible workflow. Before you can answer, your brain runs through a dozen calculations: childcare pickup, the commute from your morning meeting, whether you’ll have eaten lunch, if your partner needs the car, and how this will cascade into evening logistics. What appears to be scheduling is actually complex operational planning—and chances are, you’re doing most of it alone.

We’ve been conditioned to think of scheduling as the act of putting events on a calendar. But that’s like saying cooking is just putting food on plates. The real work happens long before anything gets written down, in what I call the shadow calendar—the invisible layer of coordination, negotiation, and mental gymnastics that makes the visible calendar possible.

The Coordination Tax

The shadow calendar starts the moment someone suggests meeting up. While they’re thinking about the event itself—the dinner, the meeting, the playdate—you’re already running calculations that would make a logistics coordinator proud. You’re cross-referencing your partner’s travel schedule with your daughter’s soccer practice, factoring in traffic patterns and your own energy levels after back-to-back client calls.

This isn’t overthinking. This is the reality of having a life with multiple moving parts, where one “yes” creates ripple effects across days or even weeks. The person suggesting the meeting doesn’t see this calculation—they just see a pause before your response, maybe interpret it as reluctance rather than the complex processing it actually is.

The shadow calendar includes all the inputs that never make it onto the actual calendar but determine everything about whether an event is feasible:

Your partner’s weird schedule that changes weekly. The fact that Tuesday afternoons drain you completely. The unspoken rule that you handle all medical appointments. The reality that “family dinner” means you’ll be cooking it. The knowledge that your mom gets anxious when plans change last-minute, so you build in buffer time for her peace of mind.

These aren’t preferences—they’re constraints. But because they’re invisible to everyone else, they become your private burden to manage.

The shadow calendar is where good intentions go to become someone else’s problem.

The Default Coordinator Emerges

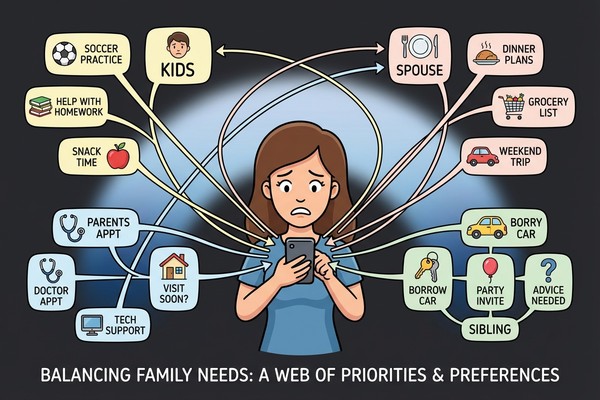

Here’s how someone becomes the family or group’s default scheduler: they start saying yes to the coordination work. They become the person who “checks with everyone” before confirming plans. They’re the one who remembers that Jake can’t do mornings and Sarah needs two weeks’ notice and the restaurant they picked last time gave Mom heartburn.

It starts innocently. You have a good memory for details. You’re naturally considerate of others’ needs. You don’t mind doing a little extra legwork to make things smooth for everyone. But coordination work has a gravitational pull—the more you do, the more gets pulled into your orbit.

Soon you’re not just managing your own calendar constraints, but holding space for everyone else’s invisible needs. You remember that your sister gets overwhelmed in loud restaurants, so you research quiet places. You know your partner’s boss tends to schedule last-minute Friday meetings, so you don’t book weekend trips too far out. You factor in your teenager’s unspoken anxiety about social events when planning family gatherings.

The insidious part is how this work gets framed as caring, as being thoughtful, as being “good at this stuff.” But what you’re actually good at is absorbing complexity so others don’t have to think about it. You’ve become a human buffer between everyone else and the messy reality of coordinating multiple lives.

The Invisible Negotiations

Every scheduling decision involves negotiations that never get acknowledged as such. When you’re “checking your calendar,” you’re often checking with multiple people, managing multiple agendas, and trying to solve a puzzle where half the pieces keep moving.

You text your partner: “Can you pick up Emma Thursday if I have a 4 PM meeting?” You’re not just asking about availability—you’re negotiating who owns the mental load of remembering pickup time, whether they’ll need to leave work early, if this creates childcare debt you’ll need to repay later.

You call your mom: “What if we do Sunday brunch instead of Saturday dinner?” You’re managing her preference for routine against your need for weekend recovery time, calculating whether the timing works with your partner’s family obligations, wondering if changing plans will stress her out more than the original timing.

These negotiations happen in the margins of other conversations, in quick texts between meetings, in the mental space you’re supposed to be using for your own priorities. Each one requires emotional labor—reading between the lines, managing reactions, finding solutions that work for everyone while protecting relationships.

The person who suggests the original meeting rarely sees these negotiations. They just get a clean “yes” or “no” answer, delivered after you’ve done the invisible work of making it possible.

The Compound Cost

The shadow calendar extracts costs that compound over time. There’s the obvious time cost—all those checking-with conversations and mental calculations. But the hidden costs run deeper.

Decision fatigue sets in when every simple scheduling question becomes a multi-variable optimization problem. You start avoiding social plans not because you don’t want to see people, but because the coordination work feels overwhelming. The mental load of holding everyone else’s constraints creates a background hum of responsibility that never turns off.

Resentment builds slowly. You notice that others can say “let me check my calendar” and actually mean checking their calendar—not running through a complex family logistics analysis. They can change plans without considering how it affects three other people’s schedules and two people’s emotional states.

When coordination becomes invisible, it becomes thankless.

There’s also the opportunity cost of your own needs getting deprioritized. When you’re optimizing for everyone else’s constraints, your own preferences become the flexible variable. You’ll take the early morning meeting because it works better for everyone else’s schedules. You’ll skip the thing you actually wanted to do because coordinating it feels like too much work on top of everything else you’re managing.

Reframing the Work

What if we stopped pretending that scheduling is simple and started acknowledging it as the operations work it actually is? In any organization, there are people whose job is coordination—project managers, executive assistants, operations specialists. They have titles, training, and recognition for this work because everyone understands it’s complex and valuable.

But in families and friend groups, we pretend this work doesn’t exist, or that it’s so natural and effortless that it doesn’t deserve recognition. We act like some people are just “naturally better” at coordinating, when what we really mean is they’re willing to absorb more complexity.

The shadow calendar represents real labor: information gathering, constraint analysis, stakeholder management, risk assessment, and contingency planning. These are legitimate skills that create genuine value. The person doing this work is essentially running operations for multiple people’s lives.

What Handoff Actually Looks Like

Handing off coordination doesn’t mean making someone else the new default scheduler. It means distributing the invisible work and making the shadow calendar visible to everyone who benefits from it.

This might look like explicitly naming the coordination work: “Before I can answer about Saturday, I need to check childcare, confirm the car situation, and see if this conflicts with Mom’s doctor appointment. Can you handle checking with your side of the family while I figure out our logistics?”

It could mean rotating who owns the coordination for different types of events, or having honest conversations about the hidden constraints everyone is managing. Maybe your partner takes ownership of their own family’s scheduling needs instead of having you manage those relationships.

The goal isn’t to eliminate the shadow calendar—complex lives require coordination. The goal is to stop pretending it doesn’t exist and ensure that the people doing this work get recognition, support, and occasional relief from being everyone’s personal logistics coordinator.

The proof that coordination is real work is how much smoother everything runs when someone’s doing it well.

The shadow calendar will always exist wherever multiple lives intersect. But it doesn’t have to live entirely in one person’s head, invisible and undervalued. When we acknowledge this work for what it is—skilled operations management—we can start distributing it more fairly and supporting the people who make everyone else’s lives run smoothly.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.