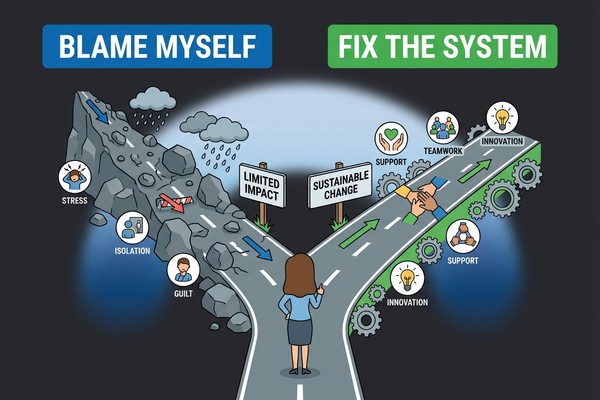

You set a goal. You fail to stick with it. The voice in your head whispers the same tired verdict: “I’m just not disciplined enough.” Or maybe it’s “I lack willpower” or “I’m too lazy.” We’ve been trained to look inward when change doesn’t stick, to excavate our character for flaws that explain why we can’t seem to follow through.

But here’s what I’ve noticed after years of watching people struggle with the same patterns: the problem is almost never you. It’s your environment. It’s the invisible friction built into your days that makes good intentions feel impossible to execute.

When someone tells me they can’t stick to their morning routine, I don’t ask about their motivation. I ask what time their kids wake up, whether they laid out their workout clothes the night before, and if their partner knows not to start conversations before 7 AM. The answers usually reveal a system designed for failure, not a person lacking discipline.

The Seductive Logic of Self-Blame

Self-blame feels logical because it’s simple. If the problem is internal—if it’s about willpower or character—then the solution should be straightforward too. Just try harder. Be more consistent. Want it more.

This narrative is everywhere in productivity culture. It’s the foundation of most self-help advice and the reason we keep buying books that promise to unlock our “inner discipline.” But it’s also deeply flawed, because it ignores how much our environment shapes our behavior.

Think about the last time you successfully changed a habit. I’m willing to bet it wasn’t because you suddenly developed superhuman willpower. More likely, something in your situation changed. You moved to a new apartment with a gym downstairs. Your schedule shifted and created a natural window for the new behavior. A friend started joining you, making it harder to skip.

The most sustainable changes happen when we redesign our environment to make the right choice easier, not when we white-knuckle our way through poor conditions.

The friction was reduced, and suddenly the behavior that felt impossible became automatic. That’s not a coincidence—that’s how behavior change actually works.

What Friction Looks Like in Real Life

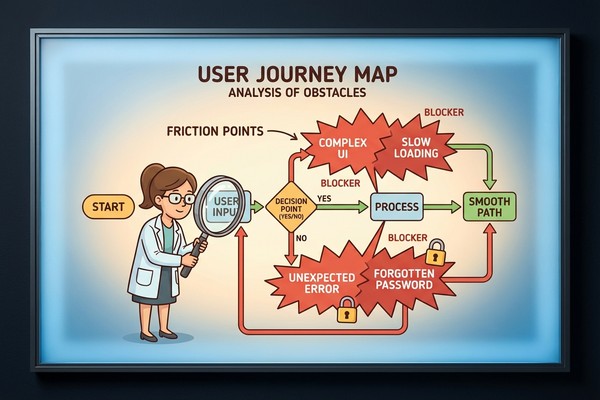

Friction isn’t just physical obstacles, though those matter too. It’s any gap between intention and action that requires extra mental or emotional energy to bridge. Sometimes it’s obvious: wanting to cook healthy meals but having an empty fridge and no meal plan. Other times it’s subtle: trying to meditate in a room where your laptop sits open, silently broadcasting your to-do list.

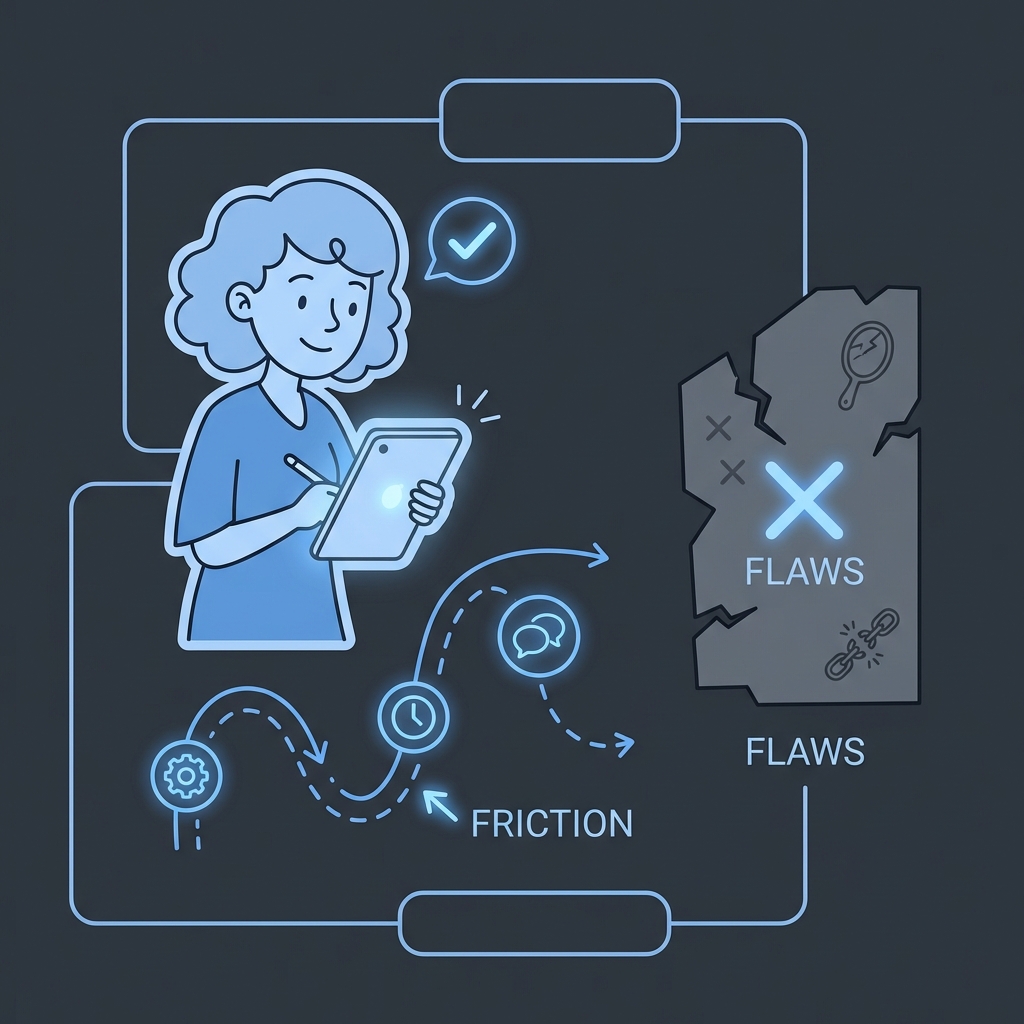

I think about friction in four categories: preparation, timing, energy, and social context. Each one can derail even the most well-intentioned efforts.

Preparation friction is having to make too many micro-decisions in the moment. You want to exercise, but first you need to find your workout clothes, figure out what routine to do, clear space in the living room, and remember where you put your water bottle. By the time you’ve handled all that, the motivation has evaporated.

Timing friction happens when you try to force new behaviors into time slots that don’t actually exist. The classic example is the parent who decides to wake up at 5 AM to exercise, forgetting that their toddler has been waking up at 5:30 AM for the past month. The math doesn’t work, but we blame ourselves for “not being a morning person” instead of acknowledging the scheduling impossibility.

Energy friction is trying to do demanding tasks when you’re already depleted. Planning to meal prep on Sunday evening after a full weekend of family activities. Scheduling important phone calls for 3 PM when you know that’s when your energy crashes. Your brain is trying to protect you by resisting these poorly timed demands, but it feels like laziness.

Social friction might be the most overlooked category. It’s trying to change in an environment where other people’s needs and expectations pull you back toward old patterns. The partner who starts conversations when you’re trying to have quiet morning time. The family that expects you to be the default dinner planner even when you’re trying to simplify meals. The coworkers who schedule meetings during your blocked focus time.

The Friction Audit

Instead of asking “Why can’t I stick to this?” try asking “What makes this harder than it needs to be?” Pick one goal or habit you’ve been struggling with and walk through these questions.

For preparation, ask yourself how many steps are required before you can actually do the thing and what decisions you have to make in the moment. For timing, consider when you’re trying to do this, what else is competing for your attention during that time, and what your energy level is typically like then. For environment, look at what in your physical space supports this behavior and what undermines it. For social context, ask who else is affected by this change and what they expect from you during this time. For competing demands, consider what usually derails this and what patterns you notice in when it works versus when it doesn’t.

The answers often reveal friction points you hadn’t considered. Maybe you keep failing to do yoga in the morning because your yoga mat is in the bedroom closet and getting it out wakes up your partner. Maybe you can’t stick to a evening skincare routine because your bathroom is where your family congregates to chat. Maybe you struggle with meal planning because you’re trying to do it when you’re hungry and tired instead of when you’re clear-headed.

Replace “I need to be more consistent” with “I need to remove obstacles.” One is a character judgment. The other is a design problem.

Once you can see the friction, you can start designing around it. This isn’t about optimizing every moment of your day—it’s about making your existing life easier to live.

Small Design Choices, Big Impact

The most effective friction reduction often comes from tiny environmental tweaks, not major lifestyle overhauls. It’s putting your vitamins next to your coffee maker instead of in the medicine cabinet. It’s setting out tomorrow’s clothes before you get tired. It’s having the difficult conversation with your family about what you need your morning routine to look like.

Sometimes it means changing when you do something rather than how you do it. The person who couldn’t stick to evening workouts but thrives with lunchtime walks. The parent who gave up on elaborate meal prep but keeps pre-washed salad ingredients and rotisserie chicken on hand for quick assembly.

Sometimes it means changing the scope. Instead of planning elaborate healthy breakfasts that require morning prep, you standardize on overnight oats with different toppings. Instead of trying to meditate for 20 minutes, you do three minutes while your coffee brews. The goal isn’t to do less—it’s to do what actually fits.

And sometimes it means getting other people on board. Having a conversation with your partner about morning routines. Asking your kids to handle their own snacks during your work-from-home focus time. Setting boundaries with colleagues about when you’re available for non-urgent requests.

Beyond Individual Friction

Here’s where most advice stops: with personal environment design. But there’s a larger pattern worth noticing. The friction in our lives isn’t random—it accumulates around the mental load we carry. The person who remembers everyone’s schedules will have more timing friction. The person who manages household logistics will have more preparation friction.

This is where tools that actually reduce mental load become valuable, not just tools that help you track and optimize what you’re already doing. When something else remembers to prep for your weekly grocery run, when your calendar automatically accounts for travel time, when follow-ups happen without you having to remember them—that’s friction reduction at the system level.

The goal isn’t to become someone who can power through any amount of friction. It’s to design a life that requires less powering through.

The shift from tracking your flaws to tracking friction isn’t just more effective—it’s more humane. It acknowledges that you’re operating within constraints, not failing to transcend them. It recognizes that sustainable change happens when we work with our reality, not against it.

Your motivation isn’t broken. Your willpower isn’t deficient. Your system just needs better design.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.