You’ve probably been told you have a “good memory” or a “bad memory” as if it’s some fixed trait you were born with—like having brown eyes or being tall. But here’s what nobody talks about: in our complex modern lives, remembering isn’t just a skill. It’s work. Cognitive labor that requires energy, attention, and mental bandwidth that could be spent elsewhere.

We’ve somehow convinced ourselves that remembering is free. That keeping track of your teenager’s orthodontist appointments, your quarterly tax deadlines, your mother’s medication schedule, and your coworker’s birthday is just part of being a responsible adult. But every time you mentally rehearse that list—don’t forget the school pickup, don’t forget the school pickup—you’re doing work. Real work that exhausts your brain just as surely as lifting boxes exhausts your back.

The Hidden Labor of Modern Memory

Think about everything you’re expected to remember on any given Tuesday. Not just your own commitments, but the invisible web of other people’s needs, deadlines, and dependencies that somehow became your responsibility to track. The permission slip that needs to be signed. The client who mentioned they’d be traveling next week. The prescription that’s running low. The anniversary you absolutely cannot forget again.

This isn’t the same kind of memory our grandparents dealt with. They had routines, seasons, communities that shared the cognitive load. We have digital calendars, notification fatigue, and the expectation that we’ll seamlessly juggle professional deadlines with personal logistics across multiple time zones and platforms.

What makes this particularly exhausting is something psychologists call prospective memory—not just remembering facts, but remembering to remember. It’s the difference between knowing your anniversary date and actually buying flowers on the right day. Between knowing you need to take medication and taking it at the right time. Between having your child’s school schedule saved somewhere and actually showing up for the parent conference.

Prospective memory isn’t just storage—it’s an active monitoring system running in the background of your consciousness.

This background monitoring is where the real work happens. Your brain constantly scans for cues, evaluates priorities, and makes split-second decisions about what needs attention now versus later. It’s like having a personal assistant who never gets to clock out, never takes vacation days, and never stops whispering reminders in your ear.

Why Reminders Aren’t Enough

The productivity industry loves to sell us on the idea that better reminders will solve our memory problems. Set more alarms! Use better apps! Color-code your calendar! But anyone who’s actually tried to manage a complex life knows that reminders are just the beginning of the work, not the end of it.

When your phone buzzes with a reminder to “call insurance company,” that notification doesn’t tell you which number to call, what information you’ll need to have ready, or how long you should expect to be on hold. It doesn’t reschedule your other commitments to make time for the call, or remember that you tried calling yesterday but their system was down.

The reminder just says: “Hey, remember that thing you need to remember to do?” And then it’s up to you to figure out all the actual doing.

This is why reminder systems often create more anxiety than relief. They turn your phone into a nagging voice that highlights everything you’re behind on without actually helping you catch up. They shift the cognitive load rather than reducing it—now instead of remembering the task, you have to remember to check your reminders, triage your notifications, and translate vague alerts into concrete actions.

The Rememberer’s Burden

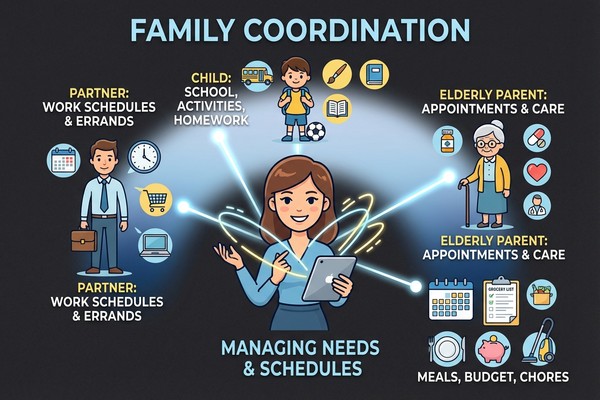

In most families and teams, there’s one person who becomes the default rememberer. The one who tracks everyone else’s schedules, anticipates what’s needed, and fills in the gaps when others forget. This person isn’t necessarily more organized or better at remembering—they’ve just accepted (or been assigned) the role of holding the group’s collective memory.

If you’re the rememberer, you know the particular exhaustion of being responsible not just for your own mental load, but for managing the overflow from everyone else’s. You remember that your partner has an early meeting so they’ll need coffee ready. You remember that your teenager has a project due and will need poster board. You remember that your aging parent mentioned feeling dizzy last week and should probably see their doctor.

The rememberer doesn’t just track information—they translate it into action. They don’t just know about the school fundraiser; they remember to send in the check, follow up if it doesn’t get processed, and coordinate with other parents about volunteer shifts. They hold not just the facts, but the entire ecosystem of follow-through that makes family and work life actually function.

Being the rememberer means carrying everyone else’s “just don’t forget” as your own cognitive load.

This role often falls disproportionately on women, who are socialized to notice needs and smooth over logistical friction. But regardless of gender, whoever becomes the rememberer in a system bears an invisible burden that rarely gets acknowledged, much less compensated or shared.

Designing for Forgetting

What if instead of trying to remember better, we designed systems that assume we’ll forget? What if we built our lives around the radical idea that human memory has limits, and those limits aren’t character flaws to overcome but constraints to design around?

This shift changes everything. Instead of setting a reminder to pay the electric bill, you set up automatic payment. Instead of trying to remember to take vitamins, you put them next to your coffee maker. Instead of expecting yourself to recall every deadline, you create systems that surface the right information at the right time without requiring you to actively monitor anything.

The goal isn’t to eliminate memory entirely—it’s to be strategic about what deserves your cognitive resources. Some things are worth remembering (your child’s favorite bedtime story, the way your partner likes their morning coffee). Other things are just administrative overhead that shouldn’t require ongoing mental energy.

Here’s a simple framework that’s helped many people think differently about their memory load:

• Remember: The meaningful, relationship-building, creative stuff that makes life rich • Record: The logistical details that need to be tracked but don’t need to live in your head • Hand off: The tasks that can be automated, delegated, or systematized entirely

This isn’t about becoming less responsible—it’s about being responsible for the right things. Your brain is not a filing cabinet. It’s not a project management system. It’s the source of your creativity, empathy, and connection with others. When it’s constantly occupied with administrative tasks, there’s less capacity left for everything that makes you human.

What Real Assistance Looks Like

The difference between a reminder and true assistance is ownership. A reminder says, “Don’t forget to do this thing.” An assistant says, “This thing is handled.”

Real assistance doesn’t just alert you to what needs attention—it takes responsibility for outcomes. It doesn’t just remind you that your car registration is expiring; it knows where you keep your insurance documents, what information the DMV will need, and how to schedule an appointment that fits your actual availability.

This level of support requires understanding context, anticipating needs, and following through on commitments. It means holding not just information, but the entire thread of responsibility from initial awareness to final completion.

The proof of good assistance isn’t what you remember—it’s what you get to forget.

When someone or something truly assists with your cognitive load, you notice not because of what happens, but because of what doesn’t happen. You don’t have that moment of panic about whether you remembered to do something important. You don’t spend mental energy rehearsing tomorrow’s to-do list. You don’t carry the low-level anxiety of wondering what you’re forgetting.

Instead, you get to be present for the conversation with your teenager. You have mental space to notice when your partner seems stressed. You can focus on the creative problem-solving that your work actually requires, rather than the administrative overhead that surrounds it.

The goal isn’t to optimize your memory or become a more efficient human. It’s to reclaim your cognitive resources for the work that only you can do—the thinking, creating, and connecting that makes your life meaningful. Everything else is just logistics, and logistics shouldn’t require the same mental energy as love.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.